What is trauma in organisations?

Trauma in organisations can show up in many guises. It can appear following a clumsy restructure, or through the long shadow cast by an unchallenged bully, or perhaps due to the loss of a colleague through illness.

These kinds of things, and others, can have a significant impact on individuals and groups. If they are not acknowledged people can feel disrespected and diminished, and triggered into passionate reactions. And it doesn’t just affect motivation. The rage and indignation people feel can limit their capacity, as they have less space to deal with tasks or solve problems.

The narratives of frustration that commonly emerge are often self limiting too: whole groups can feel victimised and rally around that identity. This group identity is powerful and can feel enormously supportive for those affected. Meanwhile those outside the group or who are perceived to threaten it (and that identity) can experience fierce resistance and challenge. These patterns, once established, can endure for years.

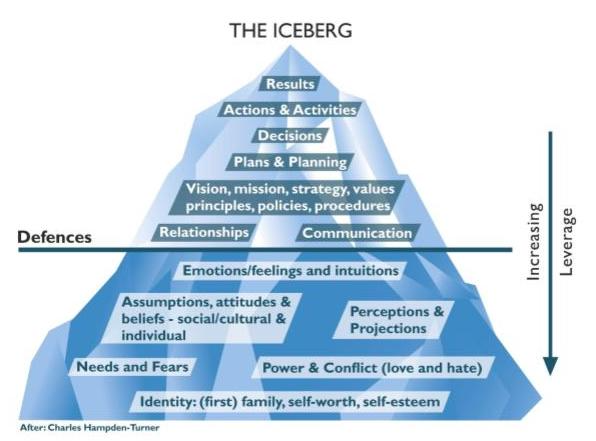

It makes sense then to pay attention to the human side of things – and the things that go on ‘below the waterline’ – especially during a reorganisation, after all 70% of change programmes fail due to employee resistance and lack of management support.

Organisational trauma has a big impact

As an example, we have been working with one institution who went through a seismic shift after a drop in numbers of international students. The leadership team was poorly equipped to deal with the resulting financial crisis and pushed through a reorganisation – downsizing the workforce, rationalising courses – to make the numbers add up, but they underestimated the harm that this caused the workforce. A failure to listen and include people led to a belief that it was all happening behind closed doors and people felt powerless to defend themselves.

As a result, a lot of tension bubbled up throughout the whole institution. Staff at all levels felt disempowered and devalued, as a consequence they could behave aggressively and unpredictably, lashing out in any direction. There was a lot of dissatisfaction, and low trust. Others at all levels were frightened to speak up or stand out on any topic, scared of making themselves a target.

You could understand, if not condone these behaviours. In truth the reorganisation was pushed through in ways that were more damaging than they needed to be. People felt they had not been listened to. They felt excluded and marginalised, their very identity threatened: they felt powerless. And then they found a way to regain that lost agency through (non physical) violence. Which reinforced an unhelpful cycle. All parties became entrenched and less open to dialogue, and everyone experienced it in ways that were detrimental.

And there will be medium to long term repercussions. There is a lot of work to do to rebuild trust.

Trauma persists even when things get better

Another of our clients experienced a similar trauma, but for different reasons. They had a comparable financial crunch, but leadership turned it around and got the organisation into a strong position. They are hiring and building teams again after a period of cutting everything.

But after a decade-long cycle of running out of money and cutting jobs every few years, some people have spent 10-years in an extended period of uncertainty, lurching from feeling at risk of redundancy and then being told their jobs are safe, and back again.

That creates trauma that has a lasting impact.

One effect is that while the new hires are coming in with enthusiasm, belief and confidence, they’re encountering a group of jaded, traumatised colleagues who do not share the excitement, and who actually mistrust everything because in their experience, new initiatives always fade into disappointment and loss.

In addition, the directive behaviours of the leadership team which were so necessary during the turnaround, are no longer a good fit. People who feel motivated to own their challenges find themselves pulled up and needing permission to act, creating the risk they will be as discouraged as those who survived the reorganisation.

Part of the issue is that there is no real acknowledgement that half the workforce are in a traumatised state – which shows up as people being slow to respond, wilfully resistant and deeply sceptical of new people.

No one is talking about it, and it’s not factored into how they’re planning changes.

Some of the new people are really sensitive to this, but the leadership team aren’t (and their expectations for the pace of change may be too high). So while some see the need to go steadily and regain trust, others are pushing hard and achieving the opposite.

What could they do instead?

In a trauma-informed approach, leaders and organisations work with the trauma to overcome the resistance that otherwise emerges in reaction. This doesn’t mean changing the outcome of decisions or the work that needs doing, it’s about how you do it.

For leaders this means:

- Recognising you have a choice to lead differently

- Being aware of what has gone on before

- Acknowledging that these things have happened

- Taking care to communicate in a way that generates psychological safety

- Demonstrating that you are listening, by making people feel heard

- Designing work to give people agency – in the way decisions are made and the way they are deployed.

Traps you could fall into

This is important work, but it is really common for people to overlook a key part of it.

We worked with one leader who badly misstepped when they arrived after a reorganisation. They had joined with excitement, enthusiasm and clarity, and said, “I know you’ve had a horrible time, but this is the turning point, let’s focus on the future, we can rebuild this.”

However their team didn’t appreciate the forced positivity, “We’re still having a terrible time! We haven’t overcome it and pretending everything is okay is not helping,” they said (to each other, but not to their new boss).

The new leader quickly lost trust and has been on the back foot ever since. It doesn’t matter what they say now, the team interprets it in a negative way – they want to blame somebody for the harm they have experienced for all those years, and it’s their new boss. This is difficult – and it’s not understood by the new leader’s peer group or their own boss, and it’s not something they can easily fix on their own. It takes a lot of work to rebuild trust.

How trauma-informed leadership can help

The process of understanding the context, empathising with people’s experience of a situation, and working through it – crucially – with them, is a way to start to change and release the trauma.

If you’re interested, our approach is to use our core toolkit for this: to help leaders respond differently by supporting them to rethink how they engage as leaders.

The support we offer is practical, emotionally informed and applied – at the core it is about experimentation, feedback and iteration.

This is not traditional training for leaders, instead it includes:

- Practising listening and talking to each other using various tools

- Applying the process to yourselves so you become a stronger team

- Helping you design how you will lead the change you want to see and taking a different approach. This means having conversations with people and involving them in how to get there.

- Helping you see your role as a convener and permission provider – learning from who you are.

- Moving from ‘we need to prioritise communicating information in scalable efficient ways’, to ‘we need to prioritise communicating information in psychologically safe ways.’

If you don’t adopt an approach like this, you will continue to come up against trauma and inertia, and will traumatise people even more.

Does this resonate with your organisation? We’d love to hear from you.

At Then Somehow we help universities and other organisations build emotional literacy, increase empathy, and help you see the world differently, giving you practical tools to shift the stuff that’s stuck.

If you’d like to discuss how we can help your organisation develop leaders and perform better, get in touch here.