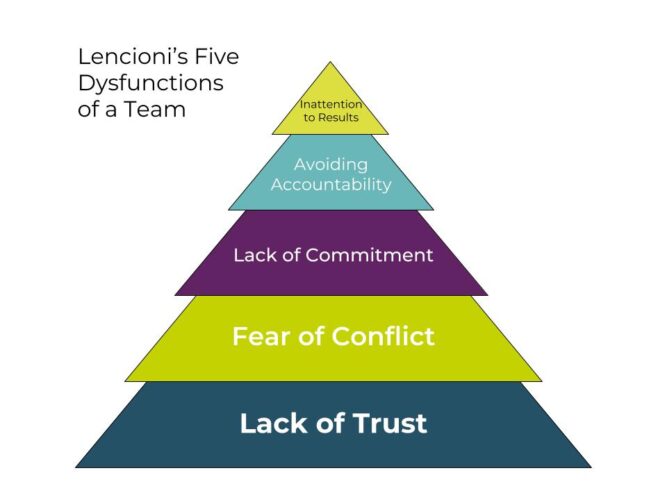

In his groundbreaking book, “The Five Dysfunctions of a Team,” writer Patrick Lencioni outlines the five basic flaws that teams commonly struggle with. They explain why building trust is one of the most fundamental things you must do to become a high performing team.

The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: An Overview

In today’s pressured Higher Education landscape, effective collaboration and teamwork are essential for achieving success. However, many professional and academic teams face challenges when it comes to working together cohesively and efficiently.

The impact of teamwork challenges means that projects or change initiatives are slowed down, abandoned or only partially completed, and people feel frustrated, lose confidence in leaders, in colleagues and in the organisation.

In his book, “The Five Dysfunctions of a Team,” Patrick Lencioni highlights several common issues that can hinder team performance. From absence of trust and fear of conflict to lack of commitment and avoidance of accountability, these dysfunctions can undermine team success.

In this article, we will delve into Lencioni’s five dysfunctions and explore strategies for overcoming them to unlock the true potential of your team. We will discuss how building trust and psychological safety within a team can foster open communication and collaboration. Moreover, we will delve into the importance of cultivating a culture of constructive conflict and embracing diverse perspectives to foster team commitment and drive innovation.

By identifying and addressing these dysfunctions head-on, you can create an environment that promotes effective collaboration, drives team engagement, and ultimately delivers results. Join us as we unlock the secrets to team success and equip you with the tools to overcome Lencioni’s dysfunctions.

Overcoming the five team dysfunctions

One of the key things we look at when we go into any organisation is team dynamics. Especially the dynamics and patterns in the leadership team. Because these patterns cascade down the organisation, causing all sorts of effects. It’s isomorphic: what happens in one place happens in another place.

If the leadership team is high performing, all well and good. But all too often they’re not.

And the reason they’re not high performing can usually be traced to the relationships between team members.

Understanding Why Teams Struggle: A Deeper Dive into Lencioni’s Model

Business writer, Patrick Lencioni’s model explains why relationship dynamics in leadership teams are so important, and the dysfunctional behaviours that cause teams to have problems. It’s a model we use a lot.

According to Lencioni, the five basic dysfunctions that teams commonly struggle with cause confusion, misunderstanding, negative morale and can impact entire organisations.

Lencioni’s Five Dysfunctions of a Team

The five dysfunctions of teams are:

1. Absence of trust

Lack of trust leads to team members being unable to be vulnerable and open with one another. This is a huge waste of time and energy, as team members invest in defensive behaviour instead, and are reluctant to ask for help from – or assist – each other.

2. Fear of conflict

Teams that are lacking trust are incapable of having an unfiltered, passionate debate about things that matter, causing team members to avoid conflict, replacing it with an artificial harmony.

3. Lack of commitment

Without conflict, it is not easy for team members to commit and buy-in to decisions, resulting in an environment where ambiguity prevails.

4. Avoidance of accountability

When teams don’t commit, you can’t have accountability: “people aren’t going to hold each other accountable if they haven’t clearly bought into the plan”.

5. Inattention to results

A team can only become results-oriented when all team members place the team’s results first. When individuals aren’t held accountable, team members naturally tend to look out for their own interests, rather than the interests of the team.

If your leadership team is struggling, it can often be traced back to these behaviours.

Recognising Dysfunctional Behaviours and How to Address Them

Often when we first work with teams we find that everybody says, “we’re good at collaborating,” but many groups are bouncing up and down between being good at working as a team, and avoiding conflict (ie preserving the status quo, which is rooted in a lack of trust) all the time.

If they can work on this, their performance as a team goes to a whole new level.

There’s a big leap you can make: if you can get better at developing skills to counter the five team dysfunctions, and change the patterns and the problems, you will build confidence and capability, become much more effective, better at collaborating, and your organisation will benefit.

It’s a slow process, but it’s worth the effort and can yield big results.

An Example of Dysfunctions in a Leadership Team

We were working with a leadership team of 15 people, within a large organisation.

All the core functions and pillars were represented in the team: marketing, research, frontline delivery, finance, HR, administration, and more.

This group wanted us to help them look at how they could work more together effectively, to strengthen their performance, and become a high performing team.

We ran various exercises with them, using tools like Timelining, Circles of Influence, Make the Boat Go Faster, to help them:

- Build trust

- Look at where they can influence change

- Discover what are the drivers and anchors for success

It so happened that they were working on an initiative to form networks of colleagues at different levels, that they could use to cross-fertilise through the organisation.

There was an earnest belief that this would be useful, and that by doing this they could dramatically improve the effectiveness of the organisation.

But you can’t legislate for how people will work within networks. They were wise enough to recognise that.

The network project was interesting, but for us the real work was: how do we use that project as a proxy to help the leadership group reflect on how they work together better as a team, especially as all kinds of interesting things happened in their attempts to do it.

Low Levels of Trust Lead to Tensions and Cracks in Teams

We ran a series of workshops that the client coordinated and pulled together, helping them to design the agendas and facilitate the sessions for the networks.

Although the intention for forming the networks was clear, to get real connectivity in each network required its participants to step into an ambiguous space. They needed to have the freedom and permission to shape the network in ways that were beneficial for them. And indirectly, therefore, for the organisation.

This was pretty high level. It’s not very directive.

But people don’t always operate well in such ambiguous spaces.

In the first network meetings, the leaders discovered low levels of trust and a lot of discomfort. There were real question marks for some people as to why they were there, and some walked out because they didn’t feel it was valuable or relevant to them.

It became apparent that there was a dearth of skills around hosting meetings, and how to create a space where people felt comfortable enough to uncross their arms and contribute.

At the meta level, the process shed real light on how the leadership team was functioning.

Tensions and little cracks were revealed between different people. Some territorial disputes emerged, some people were hesitant to participate in the project…

In the end, it all came good, but to get there required work on what a high performing team might feel like, and what they felt their dynamic was, including some self-diagnosis.

Implementing Patrick Lencioni’s team model

Six months later, we ran another session on how the network formations were going, which began very industriously because everyone was reflecting on the success of their experiments.

But when we paused the latter session and asked, “What does it reveal to you about the way that your group functions as a team?” People found that much harder.

So we worked with them to implement Lencioni’s model of Five Dysfunctions of a Team.

Unsurprisingly they all thought they were doing quite well, and to be fair, we did observe quite a significant shift in the way that they were interacting with each other from six months previously.

There was a lot more engagement in the conversation, a lot more active listening, a lot more freedom to speak, a lot less guarded-ness. You could see that trust had built in this group in that period of time.

They acknowledged this shift.

But when we pushed that further, none of them talked about the tensions that had emerged during the network project. Tensions that we were privy to because we had witnessed them.

Overcoming Fear of Conflict

This group were doing all they could to stay in a safe place and were shying away from conflict.

And by conflict, we don’t mean aggression, or people shouting at each other. Conflict is a very nuanced thing. We mean unease, tensions, the bits that aren’t vocalised but are there nonetheless.

It had been particularly noticeable during one timelining exercise early on in the process. One of the contributors had talked about how a normally joyous and significant life event was instead an awful, and dangerous one. “There was a moment when I did not know whether it was going to be okay. I was getting ready for terror,” they said.

It was the rawest moment of the day. Yet everyone went quiet, and we moved away from it.

It felt like they needed to protect this person from the feelings – a type of misplaced caretaking.

As facilitators, we needed to call this out.

We also asked the group to talk about the tensions that had emerged during the network project.

But what they shared was mostly high-level about the organisation.

The conflicts and the dynamics that had become all too obvious were still not talked about.

Building Trust: The Foundation of High-Performing Teams

There were riskier conversations to be had, so we called it out again. And slowly the penny started to drop.

“Is anybody willing to take a risk? Right now? In this group?” we asked.

Someone piped up, “Yes I can share something, but it involves another person in this room, it’s something that happened between us at our last management meeting.”

Nervous laughter. Everyone knew what they were talking about.

Someone else said, “You’re talking about me. Because I upset you when I expressed my frustration.”

You could hear a pin drop…

“I think you thought I was attacking you.“

“That’s how it felt.“

“I wasn’t. I got very frustrated with the situation, but I totally recognise you are in an impossible position. I was frustrated for you, not at you.”

At this point, the manager chipped in.

“Oh my goodness. I totally shut that down. If I’d let you carry on you’d have said that at the time and I wouldn’t have been worrying about it all week.”

As we went round the group, some were still worried about it and were still carrying the shock of that moment, even though it wasn’t even extreme.

The tension that remained wasn’t over the frustration, it was that they had visibly got upset with each other.

Recognising and addressing team dysfunction

What was the experience of talking and sharing these perspectives with the group?

“It was really good to know this person wasn’t cross with me.”

The other said, “I’m definitely going to think twice before I say anything like that again.”

We said, “No! Don’t say that! It’s okay to be angry, and you’d all benefit from talking about this. The only mistake here was the manager’s rush to smooth it over.”

We went round and asked people how they felt now, especially the ones who had nothing to do with it. Someone said, “I’m just really pleased that we’re acknowledging this. Because I’ve been thinking about it a lot.”

The manager said, “My instinct was to step in and smooth it over. Maybe what I could have done is to create the space to talk about why you felt frustrated. Other people may have also felt frustrated… it’s the frustration that we need to be talking about.”

It was a breakthrough moment for the group. The first example of the group collectively reflecting on an emotional experience, and demonstrating trust – because everyone talked about it and explored the conflict.

On one level it was a tiny thing, but symbolically it was huge – they were practising something very important. An ability to deal with conflict.

This is an example of trust building, conflict resolving, and sharing understanding that leads to a virtuous circle and a leap in performance.

It was a really important thing to talk about.

If you’d like help with issues like this in your team, at ThenSomehow we help you build emotional literacy, increase empathy, and help you see the world differently, giving you practical tools to shift the stuff that’s stuck.

If you’d like to discuss how we can help your organisation perform better, get in touch here, and if you’re looking for a way to build a feedback culture – have a look at our new 360 feedback review service: AdviceSheet.