As a manager in an organisation, awkward conversations are inevitable, but they don’t have to be a minefield.

Regardless of whether you need to hold a colleague accountable for something they did or didn’t do, tell your boss that their request is no longer possible, or confront a team member about their disrespectful behaviour, with the right approach you can successfully navigate them without feeling stressed, anxious or uncomfortable.

It may be tempting to dodge these chats, but sweeping problems under the rug is far from a solution. Surprisingly, a significant 70% of employees tend to avoid these tough talks, leading to simmering issues within teams.

A difficult conversation with your boss or colleague may be a bleak prospect, but putting it off and ignoring problems hoping they will resolve themselves can make matters worse.

For instance, not telling someone about a delay might escalate into larger issues later. Keeping quiet about concerns can lead to project failures, and unchecked disrespectful behaviour can disrupt team dynamics, turning into unhealthy conflict that can have a bigger impact on your team’s performance.

When avoiding a difficult conversation is a problem. A real life example

Consider this real-life scenario where a new manager we were supporting in a large organisation faced passive-aggressive behaviour from a senior member in their team. This team member had been passed over for promotion and was not happy: they questioned every suggestion and proposal to the point of destruction, exhausting everybody on the team.

Instead of confronting the issue, the manager tolerated the behaviour which led to unproductive conduct: the person concerned continued to sabotage everything, holding the team back and keeping everyone stuck.

We advised the manager to tell this person in a clear and respectful way that their behaviour was not okay and had to stop. They needed to say that it was affecting them, the work and everyone else too.

Unfortunately they initially didn’t feel able to – instead adopting a ‘do nothing’ strategy, something that is more common than you might think.

A fear of conflict will see people putting up with a great deal. Fierce Conversations found that the number one response to coping with toxic employees is to ignore them, with almost half hoping the issue will magically disappear.

According to a survey by Vitalsmarts the most common conversations that people tend to put off, range from dealing with rude behaviour to challenging faulty proposals and addressing incompetent colleagues.

This “do nothing” approach might seem like an easy way out but it’s far from effective. The postponed conversations result in a negative atmosphere at work where people ruminate, complain, and engage in unnecessary work, all because they’re avoiding the core issue.

Moreover, there’s a significant financial impact, with each delayed conversation estimated to cost anywhere from $100 to $5,000.

Regardless of how delicate the issue or how grim the news, the most effective approach is to address it head on and engage in a conversation with the individual involved, no matter how challenging it may seem.

In our example above, the manager finally took the initiative and calmly explained to their colleague the impact it was having on them personally. The response was dramatic. There was an apology followed by a frank and open conversation. The person’s behaviour improved, though ultimately they made the decision to leave as their frustration was with the organisation rather than with the manager.

Often embracing the conflict leads to good things. So remember, if you are faced with similar situations, think what is the best that could happen rather than the worst.

Here’s how to have difficult conversations

Mastering difficult conversations is a crucial skill for managers in any organisation. Practice is key; the more you do it, the more confident and adept you become at having the conversation with respect and honesty, which will always lead to better outcomes.

Try this 5-step framework – it will help you get better at tough talks and as you practise, your confidence will grow.

A Framework for Difficult Conversations:

- Face the situation head on

- Empathise with the other person

- Use an I-Statement

- Use the FONT tool

- Respond in a different way

Here is more information about each of these steps, with examples of how to use all the above at the end:

1. Face the situation head on

Talking about a sensitive subject can be an anxiety inducing prospect, but avoiding it only prolongs the issue. You may be worried that the other person will be defensive or won’t listen, or that they’ll be angry and aggressive. They might do any or all of these things but if you don’t try, you won’t make any progress at all. You’ll just be stuck in a difficult situation.

And you’ll probably find that it’s not nearly as bad as you imagined.

2. Prepare by empathising with the other person

There are many reasons why someone is behaving in a particular way. If they are delivering poor work, they may be struggling but be unable to ask for help. If they are not motivated, they could have issues at home. If they are being rude they may be feeling wronged by the way they’ve been treated.

Try empathising with their situation before you start talking. As their manager, your aim should be to support them while addressing their behaviour.

3. Use an I Statement

Express your feelings clearly using an “I” Statement to tell the other person how you are feeling in a clear, effective and truthful manner.

“I” Statements are a powerful way to help you express your point to someone else without causing them to feel defensive or aggressive, which allows them to respond rather than react.

The way to do this is to structure what you say in this way: “I feel X when you do Y, and [how their behaviour affects you].” For instance, say, “I feel upset when you say things like that, and this is affecting our working relationship.”

This approach fosters genuine dialogue by focusing on the consequences of behaviour rather than blaming the person.

If instead you start the conversation with the other person’s actions, or say “you make me really angry when you do X,” you’re blaming them and giving them the message that they are the problem.

NB Be careful not to turn an I-Statement into a ‘blaming-you-statement-pretending-to-be-an I-Statement. Eg “I feel that you are passive-aggressive,” is not an “I” Statement.

4. The FONT tool

FONT (Feelings, Observations, Needs, Thoughts) is a way to decode a conversation so that you understand what’s really going on for people.

Despite their importance, most people don’t bring their wants and feelings into the workplace. However you’ll find it harder to resolve an awkward conversation and increase your chances of receiving a defensive response if you attempt to handle it without discussing their needs and feelings.

FONT is a way to become more aware of what is going on, both for yourself and what you are sensing from the other person. The four categories will help you break the conversation down.

For example, I might be observing your body language and notice that you’re being defensive. I might think, “This is going to end really badly. We’re going to start shouting and she may storm out.”

With that information, I could stop trying to tell you something, and instead ask a question: “I noticed that you raised your voice when you said that. What’s going on for you? How are you feeling?”

The ultimate aim of FONT is to increase your awareness of what the other person is feeling, and to bring that into the conversation. If you can do that, you are more likely to have a much more valuable conversation.

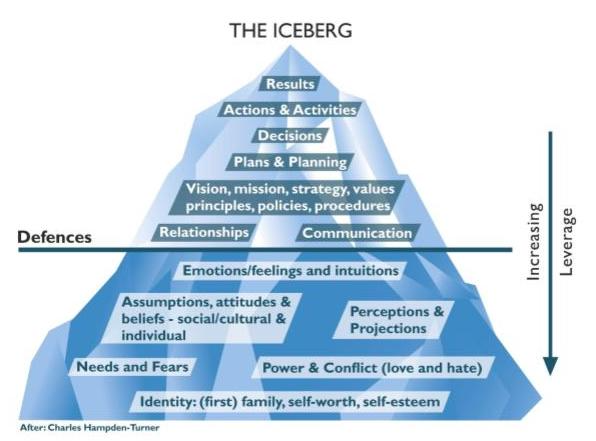

If you just stick to actions, decisions, communication and results (ie the bit above the waterline in the iceberg model, you’ll have limited leverage to change anything.

The first time you try using FONT, you may find you’re really good at working out the thoughts and observations parts, but not so good at recognising feelings or needs.

The more you practise, the more you’re able to do it on the fly.

The five core emotions

To help you identify what people are feeling, this is a helpful shortcut to use alongside FONT, the five core emotions:

- MAD (Angry)

- SAD

- GLAD

- HURT

- SCARED

If you can find a way for the person to tell you how they’re feeling, for example they might say, “I’m feeling both angry and anxious (scared),” then you might be able to empathise with them and work together to find a solution.

If their needs include being acknowledged, and a sense of feeling valued, look for opportunities to recognise them and point out their positive traits to make them feel more appreciated.

There are two ways to work with FONT:

i. In the moment

Use it to guide the conversation towards the true issue at hand. This frequently leads to a really liberating conversation. It takes practice, however your attempt won’t necessarily fail, even if it doesn’t work out the first time.

ii. Reflecting after the fact

To better understand what happened, go back over the conversation and replay it using FONT. What did you notice? What was going through your mind? What might they have been thinking? What emotions might they have had? Which needs might be motivating them?

Even if the situation fails in the moment, taking some time to reflect on what you could have done differently will help you next time, since you’ll be more prepared and be able to try something new.

Being able to say to someone, “I can see you are getting upset,” and asking, “How are you feeling?” can help to resolve the situation. If they are able to be truthful about what they’re feeling, you can say, “Okay, let’s talk about what you need.”

5. Respond with the opposite

This is an approach that’s helpful if someone is either very emotional or bombards you with facts:

- When faced with facts, respond with emotions.

- If they are very emotional, point to the facts.

Imagine an awkward conversation with a colleague who’s delivered a poor piece of work. They might start listing all of the reasons why it’s not their fault. Using facts and figures to build their case. In doing that, they’re being defensive and it will be hard to move the conversation forward. If you respond with how you feel, you can shift that dynamic. Breaking down barriers in a difficult conversation opens up possibilities for transformation.

Or perhaps the opposite happens and they start crying or become really angry. A way to respond is to, firstly, empathise with their feelings, then bring in some facts to try and get back into a conversation.

This is a useful approach if you find yourself stuck because it’s easy to remember.

Three examples of difficult situations and how to deal with them

These are examples where difficult conversations might become dysfunctional, and where people can easily become defensive:

- There is a restructure and jobs are at risk

- Someone is not doing their job properly

- A colleague is being offensive

i. People are at risk of redundancy during a restructure

If you have to restructure your team, some people’s jobs may have to be cut. People often come into those conversations with a lot of anxiety. The minute you tell them what is happening, they will be worrying about money.

Their anxiety could be unwarranted, because they may be at less risk than they think. But because they’re nervous, they may become antagonistic or aggressive. They might, for example, threaten to bring in a union rep.

What to do? Use FONT to find out what is going on for them and to reflect on what they fundamentally need.

For example, you might notice that they’re agitated, that their voice is raised and they’re being aggressive. You might be feeling nervous yourself – it is never nice to pass on this kind of news – and you might start being defensive. If the conversation spins out of control, our best advice is to stop, identify what you’re observing, and ask what they are feeling.

If they tell you they are angry after all the work they have done, calm them down by talking about what the options are. There might be options to redeploy them or a number of other roles and opportunities they could consider applying for.

Communicate what the scale of the risk is: “Even though there will not be enough posts left after the restructure, some people on the team want to leave anyway. So actually, you’re a lot less at risk than you realise. Maybe this is an opportunity, because in the new posts there are more opportunities for development. You could expect to get a pay rise.”

If their original reaction to the news was: “I am so angry because of the way this was communicated.” Their need is for an apology and a recognition of the harm that’s been done.

By addressing that need, you can move the conversation to a different place.

ii. “You are not doing your job properly, you need to improve”

Someone you are managing is performing badly. You arrange a conversation with them to discuss the situation.

You have a ‘you need to improve’ conversation but there is a thought at the back of your mind that, “this is all going to end in a formal performance management process.”

You know that’s a challenging and uncomfortable process for the person concerned and likely your relationship with them will be destroyed in the process. They’ll end up leaving anyway which may be what you really wanted, but they’re miserable and you’re miserable.

Just the thought of that could cause the conversation to be a clumsy one. However it’s avoidable if you can intervene early enough.

If you’re able to talk to them early, use The Three Key Questions to help them understand what you need and how they’re measuring up:

- Do they know what’s expected of them?

- Do they know how they’re doing? and

- Do they know where they’re heading?

In that conversation you have to be really clear about what is expected of them. Then you can monitor how they are doing, and you can identify what help they might need to do it. They’ll (hopefully) improve and you’re more likely to avoid the whole performance management process.

Win-win.

iii. A member of staff is being offensive

Sharon has made a complaint about Annie. You’ve only heard Sharon’s side of the story and you’d like to know what happened from Annie’s point of view. In this case, FONT can help you figure out what actually happened and come up with some choices for how to respond.

Annie says: “Sharon left her dirty coffee cup on the side in the kitchen. It seems a small thing but I just lost it. I shouted at her and I might have called her a rude name, because I always do the washing up – no one else does it and no one ever says thank you.”

As her manager you might say: “I’m noticing that as you talk about it your voice is raised. It seems that you’re still angry and upset about it. How’re you feeling right now?”

Annie: “Sorry. I was just so angry.”

You: “What do you need?”

Annie: “I need to not be the only person who cares about this stuff.”

You: “Did you know that Sharon had put her things in the dishwasher but it was full she had to reorganise it. Some bits didn’t fit back in so she put them on the side and put the dishwasher on, intending to come back later and finish it.”

Annie: “Oh … I didn’t know that. I’ll apologise and try not to react in future.”

You: “Thank you, that sounds good.”

In Conclusion

Difficult conversations can be daunting but there are strategies for making them better. Having read this, we hope you have more of a grasp on how to handle them, plus a couple of useful tools that you can try. With experience, difficult conversations will become easier, leading to more productive dialogues and better results.

At Then Somehow we help universities and other organisations build emotional literacy, increase empathy, and help you see the world differently, giving you practical tools to shift the stuff that’s stuck.

If you’d like to discuss how we can help your organisation develop leaders and perform better, get in touch here.